No. 23: Sub Shops, Jazz, and the Long Tradition of Hard Work

On the right side of integrity, plus Wendell Berry, Dante and definitely not Prince Harry.

👋 Happy Tuesday, friends. Happy New Year.

Here’s some of what I’m up to lately:

Writing about subs, jazz trumpet, and the cardinalest virtue;

Not caring about the Prince Harry book; and

Reading Wendell Berry and Dante.

1. A Year for Working Virtuously

A new essay:

I’d been 16 years old for less than a month, and I was irrationally embarrassed that my dad was here. It was my first week working at Firehouse Subs, ostensibly making sandwiches but literally just slicing bread and washing those clear, heavy plastic containers. I’d just secured my first W-2 job by driving east on Atlantic Boulevard and applying almost everywhere. I hoped for Publix; my reality became Firehouse.

I was near the register, Dad by the door at the other end of the red formica. He was checking on me, I know, and making small talk with the assistant manager, an ageless lady we called Miss Phyllis, who didn’t like flowers and who a month or so later would just never show up again. What she commented to my dad that I remember with a level of certainty I’d swear by in court: One elbow on the counter, talking in that parent-to-parent kind of voice, she said, “He’s the best employee we’ve ever hired.” Talking about me.

You’d think a compliment like that would be welcome, that I’d be proud or something. But it struck me then like it strikes me now: confusing, bordering on befuddling.

***

In the final week of 2022, author and anti-email activist Cal Newport published in the New Yorker a final word on the very ’22 phenomenon of “quiet quitting” and how it fits into the American social history of the life-work relationship. He casts the TikTok-based craze as just the latest episode in a long coming of age story in which we humans have to learn to live in realities of place and time and economy.

“This is why so many older people are confused by quiet quitting: It’s not meant for us,” he writes. “It’s instead the first step of a younger generation taking their turn in developing a more nuanced understanding of the role of work in their lives. Before we heap disdain on their travails, we should remember that we were all once in this same position.”

Newport recounts that before quiet quitting, millennials like him and like me thought maybe we could have a four-hour work week, which we wanted mainly to escape the Gen-X ideal of passion-following, which was itself an escape from the monotony of a Boomer’s stability fetish. And so on. Other than hopefully boxing up an over-hyped internet topic, Newport’s essay serves to remind us that for just about all Westerners, work and how we do it is almost always existential and seemingly always in need of a change.

If you’re a regular to pages and screens of Common Good, you’re familiar with some of the contours of recent work topics. Some about quiet quitting, yes. And alternatives to work-life balance (a recurring theme around here). More interestingly, we’ve kept an eye on the maturing conversation about balance, not between work and life, but between competing powers in the workplace, which includes proposals for so-called post-capitalism work culture. (For a compelling example, look at the Beloved Economies project, though you could debate whether this idea is post capitalism or actually better capitalism).

Floating around these articles and their responses, you’re likely to encounter a quote from Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life which goes, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing.” In context, Dillard is talking about the value of a schedule for her creative work and, to some extent, the function of any schedule. But as the Instagramification of her words indicates, the principle of work and time and life applies beyond that. And it makes some sense of why we humans keep thinking about and rethinking what we do and how we spend our lives. How we use them.

The conversation about how we approach our work, its evolutions and nuances, does interest me. But a lot of this of-the-moment work talk doesn’t do much to inspire me. If you know me, you know: I’ve got no intention to change the world or really anything else that peddles conference tickets or works as a slogan. Like most of you, though, I’m anxious to fill up my days with stuff that will amount to something in the end, spiritually and materially.

Strangely enough, one of the most refreshing approaches I keep coming back to comes from the inimitable Wynton Marsalis, the trumpeter and jazz guru of Lincoln Center. As I’ve talked about this before, several years ago I listened to an interview between Marsalis and actor Alec Baldwin. As it unfolds, the two start riffing on the hard work it takes to master something, acting for Baldwin and jazz for Marsalis. There’s a little about hustle in there, and dedication, but Marsalis takes it a step further. Recounting how he presses his students to master the details of their work, even when they’re the only ones who might know the difference, he says:

No one will know whether you can play these things. No one will care about that. You may be the only person you know who cares about whether you can play or not, who can evaluate your playing. Develop an independent sense of integrity and train yourself to death.

Develop an independent sense of integrity. Yes, just like any commendation of sports rhetoric, some caveats belong — like, you know, don’t die for the trumpet, and don’t let your family die for it either. But what keeps Marsalis’ comment spooling through my head is that he doesn’t mention being the best or achieving a particular status or even climbing some kind of professional ladder. Instead, he ties the pursuit of quality to integrity.

Conscientiously or not, Marsalis speaks to a way of being that resonates deeply in the Christian tradition.

The idea of integrity in your work, for Christians and nonChristians alike, comes up plenty. Clichéd, but not untrue, definitions like “integrity is what you do when no one is watching” inform a handful of principles: Don’t steal time or money from your employer by being lazy, do your part, something akin to sincerity or standing up for your beliefs. But it runs deeper than that. It goes back to Plato and Aristotle and, before them, back to Moses.

The Hebrew term for integrity speaks more to an ontological integrity, not only to the doing of the 10 Commandments but to the embodying of them. Similarly, the cardinal virtues do not include integrity, but integrity could actually describe the virtuous.

If you doubt Marsalis intended, in this somewhat random podcast interview, to invite listeners to embody whole and virtuous lives by practicing trumpet really hard, I agree with you. I think that’s actually the lesson here. In one extemporaneous comment, we sense that shortcuts hurt not only the work but reveal something about the worker, that craft and its pursuit are honorable, and that, in practice, this isn’t all that academic or ethereal. Pushing past the almost-innate impulse to just get by, even in something as normal as music lessons, captures layers of integrity: It takes personal work ethic and it taps a centuries-old way of being the world. If all that seems too earnest, too breathless for you, I don’t think it’s all that complicated.

Remember, a deadly sin is sloth. Which in our parlance means, among other things, something like “no one will know the difference.”

***

See, the reason I was so confused, befuddled, when the Firehouse Subs assistant manager told my dad I was the shop’s best hire is because I had done virtually nothing to that point. Dishes. Slicing bread. Of course, it’s possible that all Miss Phyllis was doing was talking up my dad, that it all comes down to a polite lie.

But as much as I’ve thought about this over the years, I think there’s something else to it. A week or so into my professional life, I was anything but an exemplary worker. My first attempt at sandwich-making ended with having to start over because I used too much mustard, and, I’m telling you, I hadn’t done enough for that comment to be about me. For a long time, I thought it was an indictment of most fast-casual restaurant workers, at least the ones in North Florida. And there’s still something that feels true about that. Now it strikes me that the reason for Miss Phyllis’s odd compliment — complimentgate? — may actually be simpler than I’ve been trying to make it.

This essay is up at Common Good, where it originated.

2. I have nothing more to say about Prince Harry

He’s already taken too much of our attention.

3. Here’s (some of) what I’ve been reading

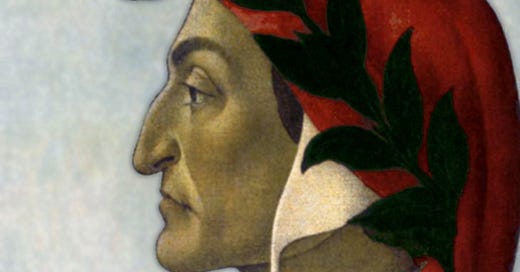

The Inferno of Dante by Dante. I’m trying to identify books I should have read that I’ve only read portions of in anthologies or not read at all. This one falls into the former, so here we are.

The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice by Wendell Berry. Elsewhere, I wrote a bit about what I read:

What won’t surprise even the casual readers of Berry is the framework of The Need to Be Whole. It’s a book, on the face, about a fairly contemporary discussion around race and American history. (As almost every review you can find highlights, Berry offers thoughts on the removal, or not, of Confederate statues.) Yet in the Berry corpus, this new title very much extends what you could call the Berry doctrine: We humans are meant to be whole, bound ontologically to our geography, ecology, economy, and theology, and attempts to disconnect any of these have cascading consequences. Into this framework, Berry places his discussion of American racism (and what he calls “race prejudice”). What doesn’t seem familiar is the product. The nearly 500 pages that comprise The Need to Be Whole seem like too many. Half of that would do. The extra pages come from some rambling treatments of topics that may distract more than add. But the last two chapters — a book-length discussion of work and a brief chapter on words — are worth the investment. And more importantly, and unsurprisingly, Berry adds a brave and distinct voice to a conversation dominated by trepidation and corporate speak.One more thing. I’m going to try to track my ’23 reading on Goodreads. I’ve never consistently used Goodreads, so I cleaned it up and we’ll just have to see how it goes. Follow along if you like, and I’ll be happy to follow your Goodreadsing, too.

👋