Issue 3 | Leave the Hot Takes Online (and Other Things I Want from Spiritual Leaders).

Writing about policing and pastors, a true crime podcast appearance, and more.

Afternoon, y’all.

Happy July. Here are five things I’ve been doing lately.

Writing about protests and pastors;

Talking about true crime and a could be-justified murder;

Returning to the beach;

Thinking about history; and

Reading Flannery O’Connor.

1. Leave the hot takes online (and other things I want from spiritual leaders).

I’ve written about five things I want from spiritual leaders, from my pastor at least, amid all this public unrest. This is a bit different for me; I generally resist the whole listicle thing, but it seemed to fit here.

Here’s the intro:

We neared downtown, and our eyes stung. Not a direct sting, but more of second-hand, nasal awareness that something essenced the air around us. The nearer we walked to the heart of the city, the more potent became the sensation of teargas.

That was a Saturday, the first Saturday after the murder of George Floyd. And almost 900 miles south of the crime scene, and about 800 miles northeast of Floyd’s hometown, people protested in Nashville, Tennessee. As the night swelled, an alert on my phone notified me about a curfew. About then, Uber and Lyft suspended service, which is how a friend and I ended up walking from midtown Nashville to our hotel downtown. We walked upstream through people rushing away from protests that had turned chaotic, riotous. We walked, with three helicopters overhead, hurrying alongside with a few others stranded on their feet. We walked toward gas and first responders and a flashing blue loud. Back in the room, the TV revealed the same scene as Nashville playing out in every major city across the United States. News anchors, local and national, were speechless, though they said a lot of words.

Of course, before the teargas and before a video of a Minneapolis policeman pressing the life out of Floyd seized the western world’s attention, the air already hung heavy. We are, after all, in the middle of a pandemic. As of this writing, the COVID-19 disease has infected 2 million people in the United States, killing at least over 115,000 people and spawning a mysterious syndrome in children. Efforts to stop the virus wrecked collateral damage to the tune of 50 million people unemployed, not including those who worked part-time jobs. We’re now officially in an economic recession. Mercifully, we can see indications that the virus is slowing, and unemployment number, for the moment, no longer appears to be in a free fall. Yet those signs feel barely relevant since Floyd’s death, since a global upheaval over American policing and American racism. “Just when things were calming down,” another friend texted me, “we got a plot twist to our dystopian movie.”

In the week that followed, protests — of police brutality, of race-based injustice within our justice systems, of the myriad and persistent ways black Americans face racism in the course of everyday life — expanded and began to take the form of marches. Millions of black Americans are expressing acute emotions, the dimensions of which I cannot comprehend. But the pain of this moment and trauma it provokes are evident. Remarkably, the demonstrations appear to have growing support among a big majority of Americans. Still, these events play out in a context that wars against solidarity. We live in a shriekingly polarized world, where political lines are drawn as quickly as they are narrowly.

Many among us struggle to make sense of the things going on around us, and likely all of us struggle to understand how to move forward in meaningful ways. A confounding reality is this: Our cities need a vibrant witness from Christians, and we Christians need our pastors. But this national calamity has taken place with our leaders and our churches reduced to YouTube channels. I’m not a pastor, but I am a Christian, a pre-COVID church-goer, who feels the weight of this moment and a responsibility to approach it Christianly. And here’s what I’m looking for from my pastor right now.

You can read the rest, if you like. Just remember it’s almost a month old at this point.

2. Is the murder of Ken Rex McElroy justified? Maybe.

Way back when, I wrote an interview column about the resurgent interest in true-crime stuff. Serial had just wrapped up (well, to whatever degree that show wraps up) and basically the whole country was in the middle of binging Making a Murderer. This week, I revisited the topic on the podcast, The Unlovely Truth. It’s here.

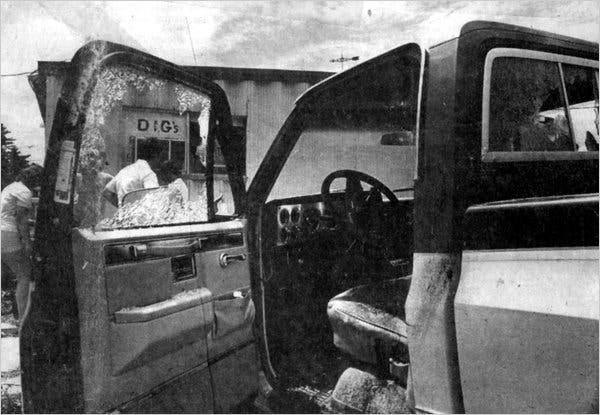

Host Lori Morrison and I talk about the endlessly complex murder of Ken Rex McElroy in Skidmore, Missouri. The man was practically a terrorist: He burned houses, stole livestock, raped at least one teenager, shot people who angered him, likely murdered at least one person, and he married four to six different women averaging 14 years old. The people in Skidmore tried the justice system, but when it didn’t work, they killed McElroy via a main-street firing squad.

We looked at the story mainly through the lens of the 1990 book In Broad Daylight. There’s also a six-part documentary about the murder called No One Saw a Thing. Hannah and I watched it and found it pretty interesting. Too, BuzzFeed has a 20ish-minute documentary about it.

Photo credit.

3. That’s Ellen and she loves the beach.

We make a point to spend at least part of each July in my home state. We can’t always make it happen, but when we do, it confirms what I tell people all the time: The shore is where I feel most at home, almost like my whole body exhales. I love it, and now my children are learning to love it, too.

4. We should take history seriously.

Since the murder of George Floyd, I’ve noticed a recurring theme at marches and in public statements: calls for white (and all) Americans to know — to learn or relearn — history. The history of racialized policing policies. The histories of men memorialized in public spaces. In short, we Americans should know our own history, not just our slogans. But this reckoning comes amid an all-out free fall in students actually studying history (along with the liberal arts broadly). And, worse, it comes in a political and social culture that overwhelmingly promotes job-getting education at the expense of historical inquiry. This affects even “general” requirements. So it’s fair to wonder if those who want to pay closer attention to history even possess the tools to do so.

5. Here’s (some of) what I’ve been reading.

Mystery and Manners. I heard about this book during an episode of the Book Review Podcast. Apparently a lot of us are having a Flannery O’Connor summer. This New Yorker piece about O’Connor’s racialized fiction got a lot of traction a few weeks ago. And this rebuttal at First Things probably didn’t, but it should have. I’ve read a good amount, though not all, of Flannery O’Connor’s fiction, but this is the fist concentrated time I’ve spent with her essays. Predictably, her cadence mirrors her fiction style, which is welcome. Here’s a line I’ve been mulling:

I have heard it said that belief in Christian dogma is a hindrance to the writer, but I myself have found nothing further from the truth. Actually, it frees the storyteller to observe. It is not a set of rules which fixes what he sees in the world. It affects his writing premiarily by guaranteeing his respect for mystery.

Abundance. I know, I know. The essay thing is maybe getting out of hand. But if you’ve not read Annie Dillard, or if you’ve only read The Writing Life, you could do worse than this collection.

Spunk and Bite. As many of you know, I’m in the early stages of writing a book. And this is one of the writing books I’ve toted to the Sunshine state. I’ve read it off-and-on for the last five years or so. It’s a different kind of writing book, a little less buttoned up and a lot into itself. And that makes it a helpful break for otherwise routine writing books.

Okay, I’ll see you in August. Happy summering.